When I’m planning a new product development schedule, I share an analogy with others: A project manager goes up to an engineer and asks them how long it will take to drive to a restaurant across town.

With a flustered look, the engineer replies:

“How could I possibly tell you that? I mean, where are you starting from? What time of day are you going? Do you even know how you’re going to get there? A car; a bus? I mean bus lines are notoriously unreliable in the morning.”

Allowing a deep breath, the project manager helps move the question forward: “Fair enough. How about we assume Thursday. Say in the afternoon? Perhaps 3pm. Let’s assume the company sedan and we’ll be starting from the company garage. How long do you think that would roughly take?

The engineer stares at them, wild eyed, visibly struggling for words.

“There’re just too many variables. I mean we don’t know the traffic light patterns. There could be construction – have you checked if there is construction on the way? What’s the condition of the car tires? Has anyone checked the weather for Thursday? The basic weather won’t do – I’d need to know the percentage precipitation for the area at that time, plus I’d have to run analysis of how much of that area we would be travelling through – and we’d need to use the upper limit of the prediction.

The Discomfort of Guessing

We’ve all been there: a project manager or a client asks, “How long will this take?” – and you, the engineer, are staring at a blank design, incomplete requirements, or an entirely new problem. Your gut reaction is “I have no clue,” but everyone is waiting for an answer. For many engineers, this situation is downright uncomfortable. We pride ourselves on precision and facts, so being asked to guess feels like stepping off a ledge. Blindfolded. What if we're wrong? What if our guess becomes a promise we can’t keep?

Being comfortable with guessing is a true engineering challenge. It goes against our training, we avoid assumptions and base decisions on data. Additionally, the decisions from those estimates have tangible consequences to business. Yet, the reality of engineering projects is that we often have to make educated guesses early on simply to move forward.

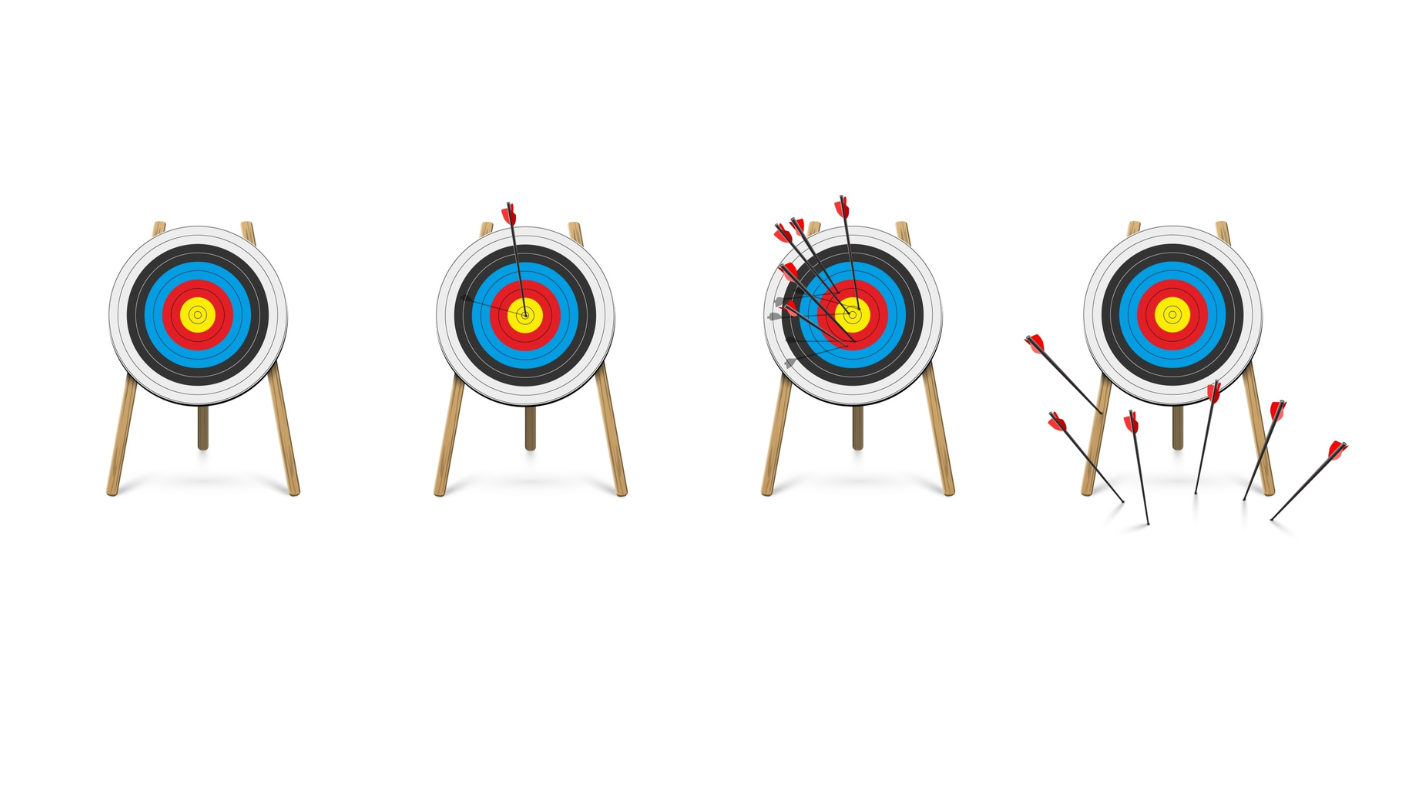

The good news is that guessing doesn’t have to feel like throwing darts in the dark. With the right mindset, approach, and honesty, we can provide useful estimates without losing our credibility.

Why Engineers Fear Guessing

We engineers are generally a risk-averse group. We like to back up our decisions with calculations, simulations, and empirical data. Guessing – especially about timelines or costs – introduces risk. If we guess too low and miss a deadline, we fear damaging our reputation or letting the team down. If we guess too high, we might overestimate the effort, potentially causing a project to be rejected or resources to be misallocated. In short, being wrong is something engineers really dislike, and a guess by definition has a high chance of being wrong.

There's also a matter of pride and perfectionism. Many of us became engineers because we appreciate logic and correctness. Providing a number that isn't rigorously justified feels like betraying those principles. On top of that, past experiences might have taught us that an “estimate” given in good faith can later be treated as a binding commitment. Once you toss out a number, decision-makers will circle it on the calendar as if it were a sure thing. That can make any engineer think twice about opening their mouth to offer a guess.

And finally, there’s the element of effort required. Based on the risk of error, and the desire to act with integrity – the effort required can feel daunting. Even worse, that effort often competes with other projects.

Why Guessing (Estimating) Matters

Despite all those fears, guessing – or more precisely, estimating – is a critical part of engineering and project planning. Early in a project, decisions need to be made: Is this idea feasible within six months? Roughly how much would it cost? Should we pursue project A or project B given limited resources? The reality is that stakeholders can’t wait until every detail is known; they need ballpark figures to plan budgets, timelines, and commitments.

Becoming Comfortable with Guessing

The opening example of the challenge estimating a drive time may be absurd, but the issue it highlights is real. If engineers are unable to provide estimates until absolute certainty is achieved, it can paralyze decision-making. If they provide estimates and they’re off, it can tangibly impact business plans. In a vacuum of information, project managers might be forced to make their own wild guesses or promises to clients – which is even more risky. As uncomfortable as it feels, our technical insight is usually the best guide for these early projections. A rough estimate from an engineer, even with plenty of caveats, is often more useful than silence or “I don’t know.” It allows the team to start somewhere and establishes a reference point that can be refined as more information becomes available.

In essence, providing an initial estimate is about communication and collaboration. It’s not about guaranteeing an outcome; it’s about giving your team a starting point. By offering a well-communicated guess, we help set expectations and shape the direction of the project. We still retain the ability to adjust course as we learn more.

SWAG vs. a SolId ENGINEERING Estimate

Not all “guesses” are created equal.

In unofficial engineering terms, you might hear the term WAG and SWAG’s.

WAG stand’s for ‘Wild-Ass Guess.’ These are shots in the dark based on little knowledge – wild estimates with little basis. It’s vital these are understood as what they are, unreliable, but at least they’re a number.

SWAG stands for ‘Scientific Wild-Ass Guess.’ It’s the kind of estimate you give when you have little concrete information – but an educated guess based on experience and intuition. A SWAG might sound like, “Probably around 3-4 months of work, but that’s a very rough guess.” It’s the best answer you can give with very limited data and is often used at the beginning of an undertaking. These should always come with a big disclaimer that they could change once you know more.

SWAG stands for ‘Scientific Wild-Ass Guess.’ It’s the kind of estimate you give when you have little concrete information – but an educated guess based on experience and intuition. A SWAG might sound like, “Probably around 3-4 months of work, but that’s a very rough guess.” It’s the best answer you can give with very limited data and is often used at the beginning of an undertaking. These should always come with a big disclaimer that they could change once you know more.

On the other end of the spectrum is what I like to call a Solid Engineering Estimate (SEE).

This is the estimate you arrive at after thoroughly understanding the problem, defining requirements, fleshing out designs, and maybe even building a prototype or two. A solid estimate is backed by calculations, past project data, or detailed task breakdowns. For example, after doing the analysis you might say, “With the design specifications now clear, we estimate 5 months of work with a 10-person team, plus a 2-week testing period followed by 6 weeks of design adjustments.” That’s far more precise and credible than a SWAG because it’s grounded in known quantities.

The key difference between a SWAG and a solid estimate is the level of certainty and detail behind the number. A SWAG is a starting point – a way to get the conversation going. A solid estimate is closer to an ending point – something you can plan around with greater confidence. Yet the effort to generate this certainty, is itself, significant.

The key difference between a SWAG and a solid estimate is the level of certainty and detail behind the number. A SWAG is a starting point – a way to get the conversation going. A solid estimate is closer to an ending point – something you can plan around with greater confidence. Yet the effort to generate this certainty, is itself, significant.

Problems arise when a SWAG is mistaken for a firm commitment. If management treats your early guess as a promise, you’re in for trouble. This is why it’s crucial to clearly label your SWAGs for what they are and push to revisit them once more facts are in.

Traps of Guessing

Guessing comes with its own set of pitfalls. Being aware of these traps helps us avoid them:

- The Overly Optimistic "Short" Guess (Underestimating): Under pressure to please or out of sheer enthusiasm, engineers sometimes give an estimate that’s way too optimistic. Guessing too short might make others happy in the moment, but it sets you up for pain later. You risk of blowing past deadlines, overworking, and disappointing everyone – including yourself is high. It’s that dreaded scenario where you say, “I can probably finish in 2 weeks,” and then reality unfolds into 4 or 6 weeks of crunch.

- The Pessimistic "Long" Guess (Overestimating): On the flip side, fear of failure and need for certainty can tempt us to err on the side of caution. Guessing too long might feel safer – after all, if you say something will take 6 months and you finish in 3, you look like a hero, right? But inflated estimates carry their own costs. A bloated timeline might cause a project to be deprioritized or canceled unnecessarily. It can lead management to assume you’re inefficient or a roadblock. Consistently overestimating can erode your credibility almost as much as underestimating it.

- Anchoring and Attachment: Once a number is out in the world, people tend to anchor to it. Even if you clearly stated that your estimate was a low-confidence SWAG, that original figure might stick in stakeholders’ minds. This anchoring effect is a trap that can haunt you. You might find that weeks later someone says, “But you said it would be done in 2 months,” even if you had a laundry list of caveats. It’s frustrating, and it’s why communication around uncertainty is so important.

- Turning Estimates into Promises: Perhaps the biggest trap is when a guess (or even a well-thought-out estimate) gets treated like a guarantee. An estimate is not a promise; it’s a prediction based on current information. However, some folks will hear an estimate and treat it as a deadline set in stone. This trap is dangerous because it discourages engineers from ever wanting to estimate again. It’s crucial for the whole team to remember that estimates can change as we discover new challenges or better solutions.

- Not Revisiting the Estimate: A guess made early in the project is almost certainly wrong to some degree – and that’s okay. The trap to avoid here is failing to update that estimate. If we cling to an initial SWAG even as the project evolves, we’re using outdated information. It’s like continuing to navigate with an old map while ignoring the signs on the road. The initial guess should be revisited and refined (turning that SWAG into a solid estimate) once you have more data. Not doing so is a missed opportunity to course correct.

Collaboration on Estimates: Engineers & PMS

Estimation shouldn’t be a battle between engineers and project managers – it should be a collaboration. Both sides play a role in making sure that guesses are used effectively and not misunderstood.

Here are some ways we can work together:

For Engineers:

- Embrace the Uncertainty (Within Reason): Accept that giving a rough estimate is sometimes part of the job. You’re not betraying engineering principles by guessing – you’re applying your expertise to give a directional Make it clear that it’s a preliminary figure, not the final word.

- Communicate Your Confidence Level: Don’t just hand over a number; provide context. Is this a wild guess with many unknowns, or a moderate estimate based on a few known factors? For example, you might say, “I’m about 50% confident it’s 3 months, given what we know now.” This signals how much salt others should take it with.

- State Assumptions and Unknowns: Briefly explain what your estimate hinges on. “That 3-month timeline assumes we get the new testing equipment on time and that the design doesn’t change mid-way.” Listing key assumptions helps everyone understand what factors could throw the estimate off.

- Understand the Definition of Done: Work never stops when the first design is complete. Consider the effort to test and correct a design. And it’s essential to consider the communication that will be required to make a design real. This is the hidden 90% of the work, and managers will look to you to know what this means.

- Give Ranges When Appropriate: If you truly have no idea whether something is 2 weeks or 10 weeks of work, it might be better to provide a range (e.g. “somewhere between 1 to 2 months”) rather than a single number. Ranges communicate uncertainty more honestly and can prevent false precision.

- Iterate and Refine: Treat estimates as living figures. As you learn more, update your estimate and promptly communicate the new outlook. Track progress and use this as guidance on the remaining estimates. Most reasonable managers prefer an updated estimate over a nasty surprise at the end.

For Project Managers (and Other Stakeholders):

- Ask for Estimates the Right Way: When you need a SWAG, make it clear you understand it’s just a rough guess. Phrase requests to acknowledge uncertainty, e.g. “I know it’s early, but do you have a ballpark figure for X?” This lets engineers know you won’t take their number as a hard promise.

- Don’t Penalize Honest Estimates: Create an environment where engineers feel safe providing estimates. If someone gives a bad guess that later needs adjustment, focus on solutions (how do we adapt?) rather than blame. Remember, an estimate that changes isn’t a failure; it’s new information.

- Use Estimates as Planning Tools, Not Gospel: It’s fine to pencil in a date based on a SWAG, but keep that date flexible. Build some buffer into schedules if possible. Communicate to higher-ups or clients that the estimate may be revised as things evolve. By treating the estimate as a guide, not a guarantee, you avoid painting the team into a corner.

- Help engineers understand the Definition of Done: It’s entirely too easy for people to think of the first pass work and plan on perfection in the first draft. Reinforcing what testing and builds will be conducted keeps the engineer thinking of the follow through work.

- Follow Up and Update: Check in periodically on how the work progresses relative to the estimate. Encourage engineers to speak up if things deviate from the original guess. It’s much easier to re-forecast mid-project than to discover at the end that you were off by a mile.

- Collaborate on Risk Mitigation: If an estimate comes with big unknowns, work together on a plan to reduce those unknowns. Perhaps allocate a short research spike to uncover critical information, or break the project into phases with separate estimates. When engineers and PMs tackle uncertainty together, the estimates get better and everyone has more confidence.

Ultimately, both engineers and project managers want the same thing – successful projects with no unpleasant surprises. That means turning guessing into a shared responsibility rather than a dreaded confrontation. When both sides understand each other’s perspectives, it’s easier to strike a balance between caution and optimism.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Becoming comfortable with guessing is about accepting uncertainty and handling it with transparency. It’s a skill that improves with practice and a healthy team culture. Summing it up, here are the key points to remember:

- An estimate is not the enemy: It’s a communication tool, not a final verdict. Even a rough estimate (SWAG) can be valuable to kickstart planning, as long as everyone remembers it’s not set in stone.

- Differentiate between a SWAG and a firm estimate: Make sure it’s clear when you’re giving a tentative ballpark figure versus a well-researched, solid estimate. Be honest when new information arises. This helps manage expectations and build trust.

- Avoid the extremes of guessing too low or too high: Aim for realism and be honest about your uncertainty. Wildly optimistic or heavily padded estimates each carry risks – instead, try to land in a reasonable range and adjust as needed.

- Communicate early and often: Don’t throw a guess over the wall and disappear. Share your reasoning, flag your confidence level, and update your estimate when new information comes in. Continuous communication keeps everyone aligned.

- Collaboration beats confrontation: Engineers and PMs should be allies in the estimation process. When you work together – sharing concerns, constraints, and updates – you turn guessing from a gamble into a manageable risk.

By fostering an environment where educated guesses are welcomed (and adjusted over time), teams can move forward with better alignment and less fear. In the end, being comfortable with guessing isn’t about loving uncertainty; it’s about learning to navigate it effectively, together as a team of problem-solvers.

– by Alex DANIELSON